Are you looking for a “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis? You’ve come to the right place. We have the best analysis you’ll find anywhere of the famous Emily Dickinson poem.

Our “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis first discusses the techniques Emily Dickinson used when she wrote the poem. Next, we do a line by line analysis of the poem. We then discuss metaphors, varying versions of the poem, and finally offer a summary.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? | Analysis of Technique

“I’m Nobody! Who are you?” makes use of so many poetic techniques that one is forced to admit that Emily Dickinson is a word acrobat. Our “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis will share with you a sampling of these techniques.

The poem contains eight lines, and we’ll refer to these lines as one to eight respectively.

First, note how many lines have internal rhymes. In line one there are “who” and “you.” In line two there are “you” and “too.” In line three there are “there” and “pair.” Even line five contains a near rhyme “dreary” and “be”.

Then there are end-of-line rhymes. The first stanza would have an a-a-b-b pattern if it were not for the final “you know” added at the end.

The second stanza’s pattern is c-d-e-d, pairing the “frog” of line two with the “bog” of line four.

If for a moment we forget about the “you know” at the end of line four, then each line of the first stanza has six beats with the exception of line one, which has seven beats. However, how was the poem intended to be read? It’s hard to say given all the dashes. With the right pauses, it’s quite possible each line could end up with the same measure of counts.

The “you know” really breaks the pattern of the first poem. It really stands out. It’s also a very colloquial expression. We think this is intentional. We feel it’s a momentary breach of the fourth wall! Suddenly the poem breaks narration and begins to speak to the reader. In fact, the reader realizes they are actually the target of the poem!

If we simply count the syllables in the second stanza, the lines don’t quite equal out, but again, we don’t know how the poem is intended to be read—just look at all the dashes! However, each line seems to drag and then punch it at the end. This is managed by both using internal rhymes, specific meters, and alliteration along with the use of harsh sounds. For example, look at line five. “How dreary—to be” has both internal rhymes and a sing-song quality to it. Just say it to yourself a few times. Contrarily, the “Somebody” comes across as a punch at the end of the line. Thus, it comes off as pompous and full of self-importance. Then in lines six and seven notice all the l-sounds giving a “la-la-la” feeling to each line, until the end, where again you get harsher sounds. Similar dynamics are at play in line eight as well.

All these techniques emphasize the meaning of the poem, which will discuss below in our “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? | Analysis of Lines 1 to 4

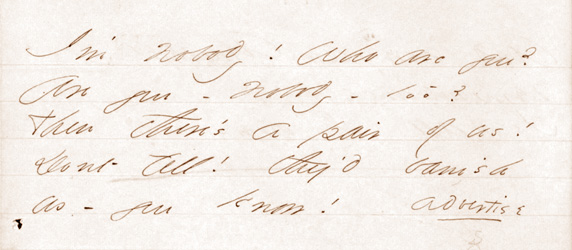

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you—Nobody—too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! they’d banish us — you know!

Out “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis starts by looking at the very first lines of the poem.

We can’t help but notice that there is a childlike quality to these words. They actually sound a bit like a whimsical adult talking down to a child. Imagine a child in the corner being ignored by all the adults—and then one of the adults, bored by the party, goes over and talks to this child. Wouldn’t this be a cutesy thing to say to this child?

We also have to note there’s an almost seductive feel to the words. They come across as an invitation to join with the narrator against boring society which has rejected this nobody.

The reference to banishment at the end of the poem is quite intriguing. If the narrator and their fellow conspirator are banished, why is this? Is it because they are nobody? But if they were banished for being nobody doesn’t that imply they were somebody after all? That is, they were identified as nobody, which suggests they must be somebody. If our analysis at this point is totally confusing you, we suggest you read up on the liar’s paradox.

At the beginning of the poem, there is a sense that the narrator is speaking to a specific person, maybe a child. We don’t know the situation or anything else about what is going on. However, at the end of the poem, we jump out of both rhythm and rhyme. The “you know” at the end speaks directly to the reader. To us, this is breaking the fourth wall. It’s saying to the reader, actually I’m talking to you.

This fascinates us, because while the initial stanza comes off as childish and playful, suddenly, we realize that we’re the child, and this comes off as potentially condescending, even elitist. The reader has to stop and think, you mean you’re talking to me? You’re saying I’m nobody like you?

I’m Nobody! Who are you? | Analysis of Lines 5 to 6

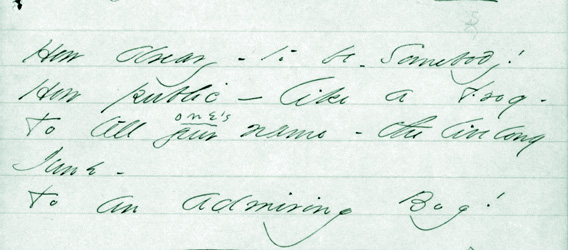

How dreary—to be—Somebody!

How public—like a Frog—

To tell your name—the livelong June—

To an admiring Bog!

Our “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis noted above that the first stanza has a conspiratorial tone, and for most of the stanza, we feel like an innocent bystander. Then the first stanza reveals itself at the end by pulling the reader into the poem. Now the narrator is directly attacking us and any notion we might have of self-importance.

This is the light in which we should view the second stanza.

Being somebody isn’t interesting at all, it’s dreary. But how could that be? Well, does anyone want to have their every move watched and scrutinized? If we are nobody, it lends us a degree of freedom that is hard to find otherwise. When there is no social pressure on us, we can be ourselves.

Someone who thinks they are somebody is all puffed up liked a frog bellowing their self-importance. People who want to be someone are show offs. Not only that, but they are not being true to their real selves. They are just putting on a phony act. Does Kim Kardashian perhaps come to mind?

The poem comes off to us as an attack on peer pressure which exists on all levels of society. Trying to fit into society nearly always stifles one’s creativity, indeed, one will find one’s spontaneity so stifled, one will feel as if they were in a bog!

I’m Nobody! Who are you? | Analysis of the Metaphors

We think the metaphor of the bog reflecting the pressures of society is fairly clear. So, in our analysis, we now want to address another important metaphor from “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” This is the metaphor of the frog.

Why is the frog used? We think this recalls, intentionally or unintentionally, the story of the Frog Prince. In that story, a princess drops her golden ball into the pond, and she asks a frog to fetch it for her. The frog agrees but only if the princess will let it spend the night on her pillow. The princess agrees but then tries to go back on the deal until her father, the king, steps in and makes her follow through. As it turns out, the frog is a prince and kissing him restores him to his true form.

Hold on to this thought for a minute, while we discuss one more thing. Why should anyone ever do the right thing? If you do the right thing only for public approval, then can you really be said to be doing the right thing? You’re motives are actually quite selfish. The only reason for ever doing the right thing is because you are trying to be true to yourself.

Just like in the story of the Frog Prince, the frog can only become someone by first being no one. That is, if a prince only acts so as to please his subjects, to conform to their will, then he is not a real prince. He’s more like a frog. In the story, the frog has to gain acceptance for who he really is via his deeds—which must be true to himself. Only then can he really be a prince. The prince must first be nobody before he can be somebody.

Our “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis leads us to think the story of the Frog Prince might contain a clue as to the poem’s deeper meaning. We will address this in our summary.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? | Analysis of the Feminist Interpretation

While we don’t feel the need to explore this topic in depth, any analysis of “I’m Nobody! Who are you? cannot ignore the context in which Emily Dickinson wrote the poem. In Emily Dickinson’s time, and in the place she lived, women were secondary. It was a male dominated culture.

Emily Dickinson was clearly an intelligent, creative individual. Yet in the later part of her life, she chose self-isolation. Why? Could it be because in the world she lived she could not be accepted for who she was? Maybe she wanted to be somebody but felt in her world she had not choice but to be nobody?

Any analysis of “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” must address this issue.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? | Analysis of Text Variations

Emily Dickinson wrote by hand “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” She left in the margins substitutions for two specific parts of the poem. We feel these substitutions would not impact our interpretation. Instead, they would be consistent with them.

Line three could be changed from “Don’t tell! they’d banish us — you know!” to “Don’t tell! they’d advertise — you know!”

The word advertise has an archaic meaning which would make it a far more clever use than banish. It can mean to both admonish and to announce. So if the public finds out that the narrator is “Nobody” they’ll be both admonished and announced (as Nobody). Do you see the irony in announcing someone as Nobody? Again, it’s the funny contradiction we mentioned in above. Ladies and Gentlemen, I present to you Nobody!

The other change is in line seven. We go from “To tell your name—the livelong June—” to “To tell one’s name—the livelong June—.” In case you missed the change, the “my” from the original is replaced with a “one’s.” We think this just makes the poem’s message more universal. The narrator is speaking to everyone and not just a particular person.

I’m Nobody! Who are you? | Analysis Summary

Our “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis reveals to us that there is a lot more going on in the poem than is initially apparent.

One analysis would be to interpret the poem in an elitist way. The narrator could be saying that it is purely plebeian and drab to want to be someone. A truly elite person doesn’t try to be Kim Kardashian but instead simply does what one must. In this case, any bit of conforming is seen in a negative light. This is elitists because democracy is always about compromise, living in society one must always compromise—conformity to an extent is necessary. Only a King or a tyrant need never conform.

But, we think the poem actually goes well beyond this. We think such an analysis would be unfair to Emily Dickinson.

It is not the crowd that is being chastised, so much as the elite themselves. The top tier of society strut about with all their self-importance, but in the end find themselves in highly restrictive environments where they must constantly sacrifice their creativity. If you don’t get this, we recommend the Edith Wharton novel, The Age of Innocence—or if you’re busy then the watch excellent movie directed by Martin Scorsese.

A conservative society heavily guided by religious precepts can be incredibly stifling. That is the society that Emily Dickinson found herself in. She could not be who she really was at all. No one really could. Everyone was trying to conform to all the expectations around them. A person with Emily Dickinson’s level of creativity and intelligence must have found this incredibly stifling.

It’s been suggested by many that Emily Dickinson at least once, and perhaps more than this, had fallen in love. Yet because of the society she lived in she potentially was not ever able to act on these feelings.

Our analysis of “I’m Nobody. Who are you?” suggests to us that the poem is actually a tragic one. It’s about the tragic loss of creativity that all of us face when we give into the society around us and deny our true inner selves. If we really want to be someone, we must all strive to be nobody. We must not give into the pressure of society, but instead we must learn to follow our own inner hearts.

We hope you enjoyed our “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” analysis. Even if you disagree with us, we hope it suggests some interesting ideas for you. Make sure to subscribe to our poetry updates or you might miss our next great analysis.