This page is an analysis of the poem Funeral Blues by W.H. Auden. The poem is also known as Stop All the Clocks. The poem became famous after it was recited in the film, Four Weddings and A Funeral. We intend to do three things in this analysis.

First, we’ll provide a brief summary of Funeral Blues that also explores the rhyming structure of the poem. Second, we’ll do an almost line by line analysis that takes into account historical context, figurative language, and any potential literary devices used. Finally, we’ll offer our interpretation of the poem. We don’t want to suggest that our interpretation is the only one, but instead, hope that we provide you with enough inspiration, so that you can formulate your own.

Summary of Funeral Blues by W H Auden

The poem is four stanzas long. It has a very simple rhyme scheme—each line rhyming with the one preceding it. Each line is approximately 10 syllables, but there is no consistency. At times an iambic pattern is used, but also not consistently. This means that the poem at times follows the traditional iambic pentameter—but not line by line. To what degree this inconsistency in meter was intentional or accidental is not clear—though we admit the inconsistency does have a way of mimicking the frantic and frenetic feeling of one facing the death of a loved one.

The mood and tone of the poem is one of grief. In the first stanza the mourning would seem to be very formal—and almost mocking in tone. In the second stanza the mourning grows to the level of hyperbole. Both the first and second stanza give one the impression that the narrator might be mocking the event.

However, when we reach the third stanza, the true mood of the poem becomes evident. We realize that the narrator personally knew the deceased. Though the comments strike a kind of formal note—coming near to perfunctory, we begin to feel their impact, especially in the last line of this stanza.

The fourth stanza is the culmination here. Clearly words are being used with hyperbole, but at the same time, they still manage to convey a deep level of grief—and the poem leaves one with the deep sense of loss felt by the narrator.

Walkthrough of Funeral Blues by W H Auden

Here we will go through the poem, almost line by line, looking at each stanza and making several points.

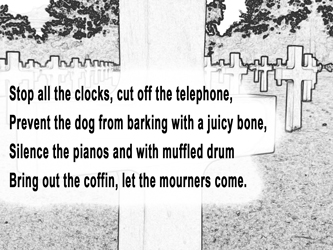

• “Stop the Clocks” is not a figure of speech. It is, in fact, an old formal custom. Once people thought it bad luck for a clock to be running with a dead person present—for example, at a wake. We’re not sure about telephones, but something analogous probably applies. If a dog barked in the background at a funeral, it was once believed that more people would be dying. The “Muffled Drum” even in the present is still a traditional custom at military funerals. Needless to say, when someone dies, you present them in a coffin for people to come in and take a look at.

• The important thing to note here is how formal all this is. No where is there anything direct in this stanza to convey grief or sadness that is personal. If anything the imagery conveys nothing but a determined attitude to do the perfunctory. To maintain the proper form and structure that society expects at someone’s death.

• Despite the non-appearance of grief, grief might be present in the following manner. How easy is it to do perfunctory matters—like send out invitations to a party? It’s not hard at all. Ostensibly, the things that must be done to prepare for a funeral shouldn’t be any harder. But, of course, they are. So behind this perfunctory attitude—we should be suspicious that their might lurk a lot grief just below the surface. We try with a vengeance to impose the normal, when what we most want to do is to hide the fact that things are not normal at all.

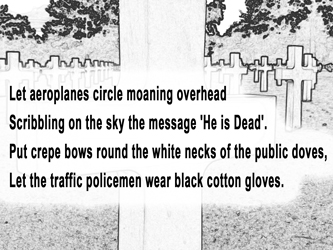

• Ostensibly, the second stanza is just a continuation of the preparations being made in the first stanza. However, we go from the trivial to the exaggerated. These requests are full of hyperbole.

• The first possibility here is the literal one. The narrator is dead serious and wants all these things done because she feels it will best represent her grief. We find this interpretation not to our liking, because it makes the narrator come across as both shallow and cheesy.

• Let’s consider a second possibility. Perhaps the narrator doesn’t care about the deceased after all. In neither the first nor second stanza has there been any direct expression of grief. Why is the narrator making such exaggerated requests? She could be poking fun at the idea of grieving for someone who doesn’t really deserve it. Could there be implicit criticism here?

• But wait, there is a third possibility, and it is the one we regard as correct. It could be that the narrator feels that no matter what is done, the funeral will never be adequate to the grief now being felt. So there is mocking criticism present, but only because it is so intense, not because it is not there at all.

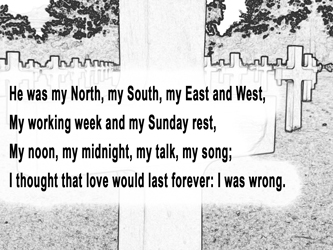

• We want to point out that the lines of the third stanza are still somewhat perfunctory because they are void of any personal elements. We know nothing of the deceased or of the narrator via these words. These lines could be for anyone—they do nothing at all to personalize either the narrator or the deceased for us.

• It is revealed in the third stanza that the deceased must be closely connected to the narrator in a personal manner. Clearly, there was some type of intimate connection between the two.

• The line, “He was my North, my South, my East and West”, conveys the loss of life direction one feels when someone important to us dies. For some this experience can be far worse than being lost in the woods without a compass.

• We’re given a sense that the narrator totally lived for the deceased. Everything they did whether in work or at play was for the deceased. This is very intense, because we have to ask, what will the narrator to do now to find meaning in life? No wonder they feel they have lost their direction without the deceased.

• The third line in this stanza is the strongest yet. It conveys that time has no meaning, and that communication is irrelevant now that the deceased is gone.

• The fourth line of this stanza is the most powerful, but also the most difficult to understand. Do we stop loving a person because they have died? Does love die when one of the lovers dies? We want to suggest that it doesn’t—and that in some ways love is forever. However, when a person close to us dies, surely it might feel as if love has died!

• The fourth line of this stanza is important, not only because of the powerful sentiment it expresses, but also because it is the point at which underlying tensions in the earlier lines are finally revealed. The first and second stanza were all about the perfunctory things that must be done to have a funeral. Even the first three lines in the third stanza were a bit like perfunctory things a person must say at funeral. But what’s said here in this last line is decidedly different. You’re not supposed to say love ends—unless you just can’t help yourself. So here, finally, the perfunctory surface has been perforated, and we see just how utterly bereaved the narrator really is—every line that’s lead up to this now makes sense.

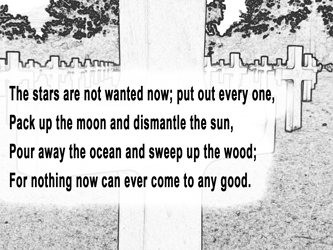

• The emotional dam bursts at the end of the third stanza, and and so now, in the fourth stanza we get an outpouring of emotion. Nothing of what’s said in the fourth stanza is perfunctory at all—contrarily, at a traditional funeral one probably isn’t supposed to speak like this at all.

• We can now see why at times in the earlier stanzas, the narrator spoke with a mocking criticism of the funeral. There is a sense that no matter what happens, the grief is too big for any funeral to adequately cover it.

• Stars here, of course, are a metaphor for all our various aspirations which guide us through life. The moon and the sun is imagery for both our heart and mind. Ocean conveys a great deepness of feeling—and while the narrator wants to reject there are any feelings worth having any more, that very rejection conveys the contrary.

• The last line here is as totally appropriate as it is inappropriate. At a funeral we’re supposed to wish for the best, stay hopeful, argue that deceased has gone on to a better world, and so on and so forth. Yet, we’re also supposed to express grief. So while the former objective here is missed, the latter is clearly achieved.

Interpretation of Funeral Blues by W. H. Auden

Funeral Blues by W. H. Auden is a rich and beautiful poem. It adeptly makes use of the perfunctory to convey deep grief. This is done via a fascinating juxtaposition. At the beginning of the poem the narrator is determined to do everything right—and to have an appropriate funeral. But they go too far in this, leading to hyperbole—which begins to make us suspect how deep their grief really goes. When the narrator begins to offer us some words of grief, while here too, those words start out by merely expressing some perfunctory sentiments, soon the real grief of the narrator takes over—and via the breaking of the perfunctory, we see just how genuinely bereaved the narrator is.

We hope you found this analysis instructive. Don’t forget to subscribe to our poetry updates, so that you don’t miss any of our original poems and analyses.